Fall has finally arrived here in Encinitas. Shorts are being traded for jeans, full wetsuits are coming out of the closet, and we even might get a dusting of snow in the Sierras this weekend. For some reason, the stock market usually treats the change in seasons badly, with September being historically the worst performing month for the market (there’s even a term for it, the September Effect). This month has been no different.

Last four Septembers for the S&P:

2020: -3.92%

2021: -4.76%

2022: -9.34%

2023: -5.19% (thru 9/26)

Last three Q4s:

2020: +11.69%

2021: +10.65%

2022: +7.08%

2023: ?

Let’s hope the 4th quarter continues the trend.

Why did the market sell off this month? Primarily the continued rise in long-term interest rates. After the September meeting and some stronger than expected economic data, the market is coming to the realization that interest rates might stay elevated for some time. In certain cases, they’re as high as they’ve been in decades.

This is causing quite a divergence in the economy. Americans that own their home and are savers? Yes, inflation has impacted everyone’s bottom line but they’re in as good of a position as they can be. Savers can now buy that 1-year treasury note for almost 5.5% – the highest in 23 years and a welcome change for earning almost zero for so long. Debt as a percentage of household income is also only back to average levels of the past decade and still lower than before the financial crisis.

The same goes for big corporations as well. We wrote in July that they were able to refinance their own debt before rates rose and shield themselves from higher borrowing costs. Now they’re in even better shape as they earn more money on the cash on their balance sheets.

The winners from higher rates were high-quality borrowers, who locked in low interest rates around the pandemic with bonds maturing further in the future than anytime in history. Higher rates have little immediate impact on their borrowing costs – only affecting bonds when they are refinanced – while they earn more on their cash piles straight away.

Take Microsoft, the world’s second-most valuable company. It has more cash and short-term investments than debt, so it was never going to be threatened by higher rates. But it also fixed its borrowing costs; it paid exactly the same interest, $492 million, in the latest quarter as a year earlier. However, it earned substantially more on its cash and short-term investments, with the annualized rate rising to about 3.3% from 2.1%; combined with a small increase in its hoard to $111 billion, it earned $905 million in interest just in the quarter, up from $552 million.

Microsoft’s experience appears to be reflected economywide.

Rising Rates Make Big Companies Even Richer

This might explain why the stock market is up on the year in the midst of all the other issues we’re having in the economy. The S&P 500 is dominated by these big companies.

Unfortunately it’s the opposite for those on the other side of the spectrum. As we wrote last month, it’s a bad time to be a borrower. Higher interest rates are really starting to impact consumers.

Buying a home or car right now is “completely unaffordable for the American household because you’re mixing the higher borrowing costs with the high prices,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

He estimates that the typical American household would need to use 42 weeks of income to buy a new car, up from 33 weeks three years ago. The National Association of Realtors calculates that the typical American family can’t afford to buy a median-priced home.

Americans Finally Start to Feel the Sting From the Fed’s Rate Hikes

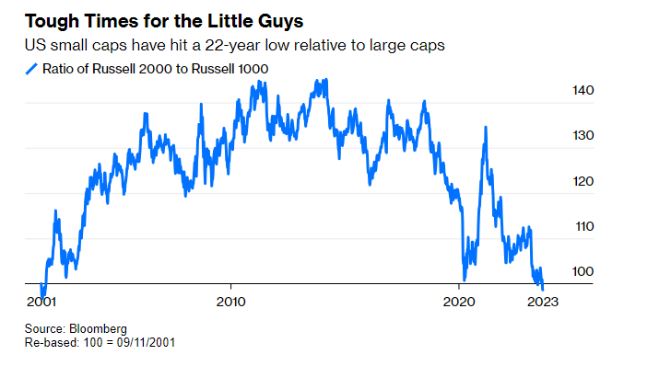

This extends to smaller companies as well, who have to rely more on debt than larger ones. Smaller companies, or small caps, used to compensate you for the extra risk you take by investing in them with higher returns. This has not been the case lately as their relative performance vs. larger companies is now at a 22-year low.

It’s hard to say where we go from here but it’s safe to say we’ll be digesting our new normal, or “new abnormal”, for the near future. Again, from the WSJ:

Until then, we live in strange times. Rising rates make a big part of the economy feel richer – not poorer.